Qualitative - Data Analysis

Week 5 + 6 - Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis: One of the major paradigms in LIS research is the collection and analysis of data using qualitative methods. In this two week class session we will discuss data collection methods like interviews, surveys, and content analysis. We will also discuss analytic techniques such as interview coding, memo writing, and ethnographic reporting.

Introduction

Thus far we have viewed LIS research as moving progressively through stages - going from Planning to Design to Execution.

At the Execution stage of a research project we find ourselves simultaneously engaged in the collection and analysis of data. If we borrow some of the phrasings from our conceptual foundations for research -we are beginning to gather justification (analyzed data) for our beliefs.

In qualitative data collection and analysis - the Execution stage - it can often feel like the progressive move towards a confirmation of our beliefs is actually circular. That is, when we approach an open ended research questions that depend on pattern making and hypothesis generation it can often feel like we are going ‘round and round’ trying to figure out what a reasonable generalization from data to hypothesis might actually be. For example, we may have one working explanation from doing three participant observation site visits, and on the fourth visit observe something that completely changes what we had previously thought was a general explanation. We might, to use our running example, observe a high school cafeteria where every Friday all students decide to sit at different lunch tables. This would complicate how we viewed the cafeteria as a site where social bonds are formed.

The good news is that this circularity of interpretation and meaning making is perfectly ok. In fact, this is how induction is supposed to work; we move from observations to certainty through reflecting on and revisiting data that we collect over time. The bad news is that it takes much patience to do qualitative data analysis well. Moving from observation to explanation requires revisiting, revising, and reviewing data - and this takes a lot of care and patience.

Data Analysis

Data analysis then is about organizing and structuring our data to justify beliefs that we hold as a result.

In qualitative research the data that we collect often results from what someone said (interview transcript), reported (free response in survey), documents they created (objects that are interpreted), or what we observed (field notes). Thus, we need a method for transforming these observations into empirical generalizations (hypotheses).

How we begin to generalize from this data is closely related to what we accept as JUSTIFICATION for what we believe…

- If a “truth” exists… we begin our analysis looking for evidence that supports or rejects our hypothesis. (deduction)

- If there are many possible truths … we begin our analysis looking to generate a range of possible explanations. (induction). If working from an inductive standpoint the process we are involved in is about abstraction; We want to abstract away from particulars to generalize explanations for how or why something happened the way that it did. Another way to say this is we are producing a finding through our analysis.

Codes, Coding, and Codebooks

If data analysis is about organizing and structuring our data to justify beliefs that we hold as a result, then qualitative data analysis requires that we structured interviews, documents, and other notes for structured interpretation. The activity of ‘structured interpretation’ can be thought of, generally, as pattern making or coding.

A succinct set of definitions for how qualitative scholars think about coding is as follows:

- Codes are shorthand notation for themes that are reflected in data. Themes enable us to move from particular examples to generalizations

- Coding is the act of linking themes (codes) with passages of qualitative data

- Codebook is a list of codes and their definitions. Importantly, codebooks offer instructions on how and when (and when not) to apply codes.

The order in which we develop codes and codebooks is closely tied to which paradigm you are aligned:

-

If working from an inductive logic then the codes will be developed during the process of interpretation. Sometimes qualitative researchers refer to this as the codes “emerging” from the data.

-

If working from a deductive logic researchers will develop a codebook in advance and look for confirmation or rejection of our hypothesis based on data analysis

Just as with data collection the two approaches could not be more different - each approach - deductive or inductive depends upon a logic that orders the procedures of data analysis.

Types of Codes

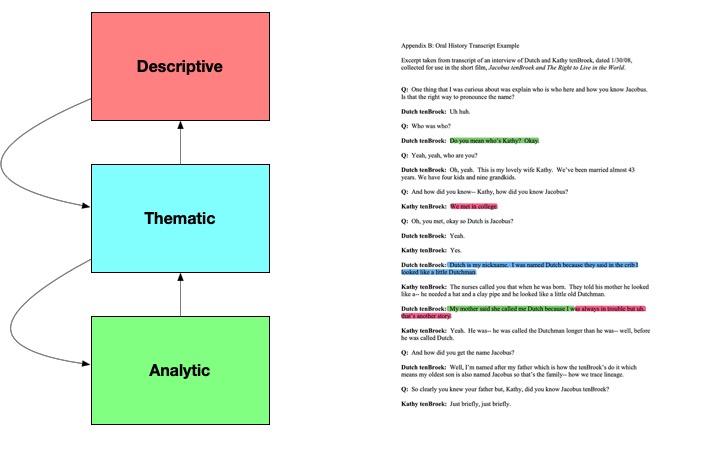

In the process of applying a code qualitative research requires multiple passes or readings. Over time qualitative scholars have named these readings and described their role in moving from observation to explanation:

-

Descriptive or structural codes are the first pass that one makes in coding. Descriptive codes are used to pick out and name characteristics of the data and its subjects - answering questions like who, what where, and how the data were collected

-

Topic or thematic codes are often the second pass in generating codes inductively. The second coding pass is used to describe the topic or a theme being discussed. It’s important to note that any passage can include several topics or themes. The topics or themes can be pre-existing or borrowed from previous research, or they can be generated newly from your research (de-novo)

-

Analytic codes are the final pass that one makes in qualitative analysis. Analytic codes are meant to apply a final version of a codebook, pursue comparisons between codes, seek explanations that are summative, and create a logic that links codes to research questions. At the analytic stage we discussed two techniques for either Splitting codes when the topic is too broad to be contained in a single code, and Lumping when a code is too narrow to fully explain a broader concept.

Codebooks

Developing a codebook is necessary to document and make clear the logic behind a coding process. Often, a codebook will need to be drafted and then updated as changes, refinements, and improvements are made to the definition of a code. At minimum a codebook should include a definition of what the code means, an application direction for when and how the code is to be applied, and an example. The following is an entry in a codebook from data used in lecture this week:

| Code | Parent-Child Communication |

|---|---|

| Definition | How parents describe the way they talk to or engage in conversation with their children about topics relevant to education, discipline, and violence |

| How code should be applied | Use this code only when a parent explicitly describes communication. This is not the same as communication between school / teacher and parent. |

| Examples | “We think that sometimes as parents, we don’t talk about violence to our sons” [Int-01] |

When does qualitative data analysis stop?

We’ve talked about how to code, and what to code - but we haven’t necessarily described what it looks like to finish coding a research project. Recall, we opened the chapter by describing induction as a somewhat circular process - requiring that we revisit data and revise our interpretations over time. When qualitative scholars describe the process of completing analysis it is often through a metaphor of “saturation” - that is, the researcher has reached a point at which no new information can be gleaned from analysis. This sounds inexact (and it admittedly is), but one way to understand saturation is to view your qualitative data as texts to be read and interpreted. When we have read a set of transcripts enough that we stop applying codes, our codebooks have stopped being refined, and we no longer see the need to lump or split codes - we have likely reached saturation. At that point we can beginning to write the results of our research into a narrative where codes, participant quotes, and other anecdotes from our data collection can be used to answer research questions (and justify our beliefs).

Readings

- Gibbs, G. R. (2007). Thematic coding and categorizing. Analyzing qualitative data, 703, 38-56. PDF

LIS Spotlights

Instead of just one LIS Spotlight this week you can choose from any of the four below -based on your interest in different methods.

Interview:

- Zavala, J., Migoni, A. A., Caswell, M., Geraci, N., & Cifor, M. (2017). ‘A process where we’re all at the table’: community archives challenging dominant modes of archival practice. Archives and Manuscripts, 45(3), 202-215. PDF

Ethnography:

- Lee, W.-C. (2019). Cataloging practices through an ethnographic lens: Workarounds, disagreements, and manifestations of culture. In Proceedings from North American Symposium of Knowledge Organization, vol. 7. (pp. 129-137). (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania). PDF

Document / Content Analysis:

- Cohen, R., Irwin, L., Newton-John, T., & Slater, A. (2019). # bodypositivity: A content analysis of body positive accounts on Instagram. Body image, 29, 47-57. PDF

Mixed Methods:

- Price, L. (2019, June). Fandom, Folksonomies and Creativity: the case of the Archive of Our Own. In The Human Position in an Artificial World: Creativity, Ethics and AI in Knowledge Organization (pp. 11-37). Ergon-Verlag. DocX

Recommended

- Vaughn, P., & Turner, C. (2016). Decoding via coding: Analyzing qualitative text data through thematic coding and survey methodologies. Journal of Library Administration, 56(1), 41-51. PDF [Focused on Library Administrators]

- Carpendale, S., Knudsen, S., Thudt, A., & Hinrichs, U. (2017, October). Analyzing qualitative data. In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM International Conference on Interactive Surfaces and Spaces (pp. 477-481). PDF [Focused on Researchers and HCI / Systems Developers]

- McDonald, N., Schoenebeck, S., & Forte, A. (2019). Reliability and inter-rater reliability in qualitative research: Norms and guidelines for CSCW and HCI practice. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 3(CSCW), 1-23. PDF [Focused on a narrow topic (inter-rater reliability) but very helpful for coding in teams]

Exercise

The exercise this week focuses on qualitatively coding data. This file contains a free response question found on a survey of 500 K-12 educators. The survey was distributed on 12.2010 in Bloomington IN at an educational conference. The participants, who are all teachers, are responding to the question “What major factors led you into teaching?”

Here are your instructions:

- Begin by thematically coding responses from each participant

- After the first 30 responses, try to develop just 5 codes that categorize “factors” that led a person to pursue teaching. You made to revise these codes by lumping or splitting the codes.

- Apply the 5 codes to 50 more responses.

- Continue to do this until your five codes seem stable - then give them a definition.

- You may want to follow the conventions that we described in class for a codebook (a definition, an application, and an example)

Bring your codes to class next week for discussion.